Author: Marita Bradshaw and Mike Smith, National Rock Garden Steering Committee

Extract from National Rock Garden Newsletter No. 22, December 2021

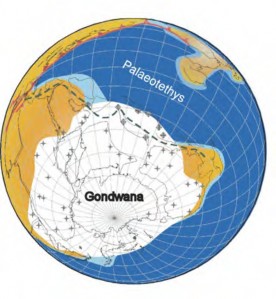

In the festive season thoughts tend towards warm summer days and iced beverages but cast your mind back around 300 million years to when there was a lot more ice around and nothing bottled to pour it over. Australia and much of Gondwana was in the grip of a major ice age, that took hold in the Late Carboniferous and extended well into the Permian as ice sheets advanced and retreated several times across the great southern landmass. This was the last major glaciation on the Australian continent, in contrast to Northern Europe and America where the ice began to retreat only around 15,000 years ago. There are several locations where you can see the record of Australia’s last major ice age in situ in national parks and reserves; and plans are underway to gather some exhibits for the National Rock Garden that represent this dramatic time in Australia’s geological history.

Permian glacially influenced sediments, sometimes kilometres thick, are found in all Australian states. There were large ice sheets, smaller valley glaciers, glacial lakes and outwash plains, and where the ice meet the sea, floating ice shelves. Sediments were delivered to many different basins where they were deposited under a variety of terrestrial and marine conditions. Examples of rocks that record some of these icy environments are described below.

Tallong Conglomerate, Sydney Basin, NSW

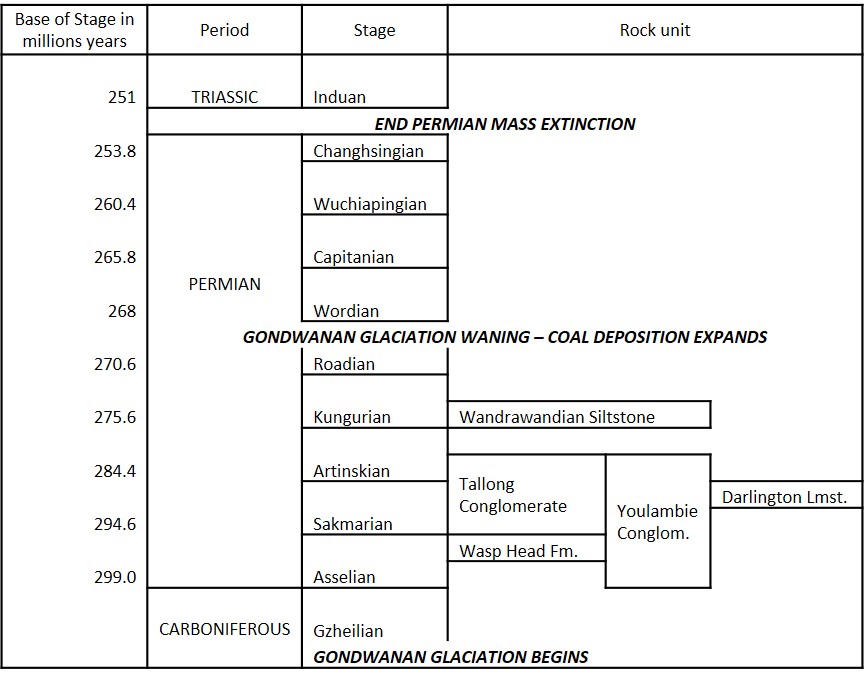

The earliest rocks deposited in the Sydney Basin are coarse conglomerates and sandstones of Early Permian age (around 295 to 280 million years ago) that fill valleys cut into older bedrock along the western basin margin. Some of these channels extend eastward for 50 km or more and are thought to be the product of ice and meltwater from alpine glaciers (Herbert & Helby,1980; Bembrick, 2015). The Talllong Conglomerate is one of these units that has been mapped as a palaeovalley deposit, 3-4 km wide, some 100 km long and over 200m thick. In outcrop the Tallong forms cliffs of well lithified, poorly to moderately sorted conglomerate and sandstone interbeds. It is made up of rounded to angular cobbles and pebbles and both clast- supported and matrix-supported fabrics are seen. The cobbles are a mixture of rock types including quartzite, sandstone, vein quartz, chert and volcanics (Trigg & Campbell, 2016).

Wandrawandian Siltstone, Sydney Basin, NSW

Further out into the basin finer sediments were deposited where glacial outwash rivers met the sea. Boulders sitting isolated in mudstone show that the ice did reach the sea at some times and in some places. Such ice-rafted “dropstones” fell to the muddy seabed as floating ice melted that still entrained some larger rocks from onshore. The Wandrawandian Siltstone that outcrops on the coast near Ulladulla is an example of a glacially influenced Permian fine-grained marine unit. The Siltstone is late Early Permian in age (Kungurian) and is younger than the Tallong Conglomerate (Sakmarian to Artinskian) and was deposited past the peak of the Gondwanan glaciation, but there was still ice in the landscape (Fielding et al, 2008).

In addition to scattered dropstones, the Wandrawandian Siltstone preserves a variety of fossils that have been described as a cold-water fauna. These include crinoids (sea lilies), bryozoans, brachiopods, and molluscs; as well trace fossils of tracks and feeding trails left behind by creatures that lived on the seafloor and in the sediment some 270 million years ago. Another indication that the ice was not too far away is the occurrence of glendonites – pseudomorphs after ikaite, mineral carbonate crystals that grew within cold (<7°C) soft mud of the seabed (Thomas et al, 2007).

On the rock platform at Ulladulla, you can step back into the icy world of Gondwana by taking a Guided Fossil Walk, recommencing in December 2021. Please see the website for details.

Basal Beds (Darlington Limestone) Fossil Cliffs, Maria Island, Tasmania

The Gondwanan continents shared not only ice sheets but also the cold-water fossil Eurydesma, a big, thick shelled bivalve that has been recorded in Permian glacial deposits from Australia, India, South Africa and South America (Runnegar, 1979). One of the most spectacular outcrops of these fossils is to be found on Maria Island, Tasmania. Here the shells of Eurydesma, spiriferid brachiopods and other marine invertebrates are so densely packed that they were once mined for cement. Among the shells are occasional cobbles of granite and other rocks. The shells beds are interpreted as subtidal shell banks that accumulated during a waning phase of the Permian glaciation, when there was still occasional sea ice (Fielding et al, 2010; Isbell et al, 2013). This world-class fossil site is now within the Maria Island National Park and can be accessed on a walking trail, please see the website for details https://parks.tas.gov.au/explore-our-parks/maria-island-national-park/fossil-cliffs.

Another place to see the story of Australia under ice is Hallett Cove, a coastal suburb of Adelaide, South Australia. An interpretative walking trail that leads the visitor through the geology that displays both erosional (ice-polished Neoproterozoic bedrock pavements) and depositional evidence (Cape Jervis Formation diamictite) of the Gondwanan glaciation (Preiss, 2019). Details about the Hallett Cove Conservation Park can be found at this website https://www.parks.sa.gov.au/parks/hallett-cove-conservation-park.

In Queensland, Late Carboniferous to Early Permian glacial sediments are recognised in the Bowen and Galilee basins, and in the Yarrol Block of the New England Fold Belt where the polymictic Youlambie Conglomerate outcrops. This conglomerate was deposited in the Early Permian (Asselian to Sakmarian) as a glacier advanced into a lake system (Jones & Fielding, 2004).

Near Bacchus Marsh, Victoria there is outcrop of glacially influenced sediments that include diamictite, massive sandstone, interbedded dolomitic sandstone and siltstone, and matrix-supported conglomerate. These are facies of the Bacchus Marsh Formation which was deposited in the late Sakmarian an inland sea that developed as the ice sheets retreated southwards (Webb & Spence, 2008).

The extensive ice sheet that covered much of Western Australia in the Carboniferous and Permian delivered thick sediments to the Perth, Carnarvon, Canning, Bonaparte and Gunbarrel/Officer basins. There are examples of striated pavements, diamictites, mudstones with dropstones and possible glacial varves (Mory et al, 2008).

References

Bembrick, C., 2015. Geology of the Blue Mountains, with reference to Cox’s Road. Available at https://coxsroaddreaming.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Geol-Blue-Mtns_CSB_edited.pdf

Fielding, C.R., Frank, T.D., Birgenheier, L.P., Rygel, M.C., Jones, A.T. and Roberts, J., 2008. Stratigraphic imprint of the Late Palaeozoic Ice Age in eastern Australia: a record of alternating glacial and nonglacial climate regime, Geological Society of London. Journal, 165, p129-140. https://doi.org/10.1144/0016-76492007-036

Fielding, C. R., Frank, T. D., Isbell, J. L., Henry, L.C. and Domack, E. W., 2010. Stratigraphic signature of the late Palaeozoic Ice Age in the Parmeener Supergroup of Tasmania, SE Australia, and inter-regional comparisons. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 298, 70–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.05.023

Herbert, C and Helby, R., 1980. A Guide to the Sydney Basin., Geological Survey of NSW. Bulletin Number 26.

Isbell, J.L., l. C. Henry, I.C., Reid, C.M. and Fraiser, M.L., 2013. Sedimentology and palaeoecology of lonestone- bearing mixed clastic rocks and cold-water carbonates of the Lower Permian Basal Beds at Fossil Cliffs, Maria Island, Tasmania (Australia): Insight into the initial decline of the late Palaeozoic ice age. In Gasiewicz, A. & Słowakiewicz, M. (eds) 2013. Palaeozoic Climate Cycles: Their Evolutionary and Sedimentological Impact. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 376, 307–341. http://dx.doi.org/10.1144/SP376.2 #The Geological Society of London 2013.

Jones, A.T. and Fielding, C.R., 2004. Sedimentological record of the late Paleozoic glaciation in Queensland, Australia. Geology, 32 (2). 153pp. https://doi.org/10.1130/G20112.1

Mory, A.J., Redfern, J. and Martin, J.R., 2008. A review of Permian–Carboniferous glacial deposits in Western Australia. Special Paper of the Geological Society of America, 441, 29-40. https://doi.org/10.1130/2008.2441(02)

Preiss. W., 2019. A new geological map of Hallett Cove. MESA Journal 91 2019 – Issue 3, p33–50. https://energymining.sa.gov.au/minerals/knowledge_centre/mesa_journal/previous_feature_articles/new_hallett_co ve_geological_map

Runnegar, B.,1979. Ecology of Eurydesma and the Eurydesma fauna, Permian of eastern Australia, Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology, 3:4, 261-285. https://doi.org/10.1080/03115517908527798

Thomas, S.G., Fielding, C.R. and Frank, T. D., 2007. Lithostratigraphy of the late Early Permian (Kungurian) Wandrawandian Siltstone, New South Wales: Record of glaciation? Australian Journal of Earth Sciences, 54(8), 1057-1071. https://doi.org/10.1080/08120090701615717

Webb, J.A. and Spence, E., 2008. Glaciomarine Early Permian Strata at Bacchus Marsh, Central Victoria – The Final Phase of Late Palaeozoic Glaciation in Southern Australia. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 120(1): 373–388. ISSN 0035‑9211.

Trigg, S.J., Campbell, and L.M., 2016. Moss Vale 1:100 000 geological sheet 8928. Explanatory Notes, Geological Survey of New South Wales, 268p

Yeh, M.-W. and Shellnutt, J. G., 2016. The initial break-up of Pangaea elicited by Late Paleozoic deglaciation. Sci. Rep. 6, 31442. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep31442