Introduction

Sydney, the harbourside capital of NSW, is a city founded and excavated in sandstone, partly built with sandstone materials, and set in a sandstone-dominated landscape. Sandstone is therefore the one rock type that every Sydney resident can confidently identify. It is the rock in ‘The Rocks’, the historic tourist precinct beside the harbour. It underlies and shapes our scenery: the vertical cliffs, the plateau surfaces, the steep and boulder slopes, the narrow drowned valleys and the shallow soils.

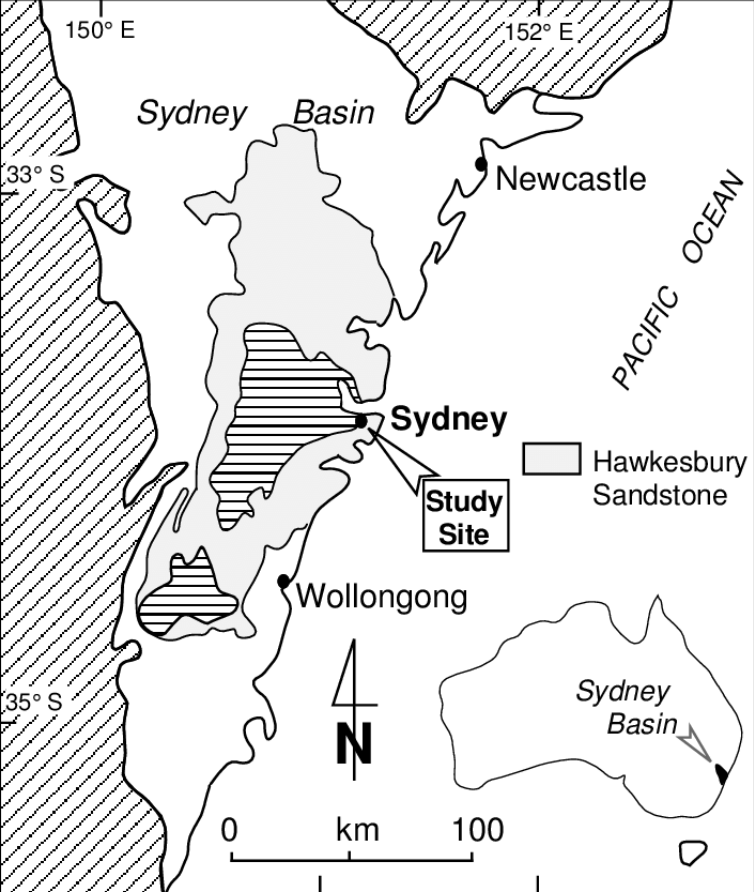

Sandstone is the principal rock type in the Sydney Basin, making up more than half of the sedimentary sequence, and the most prominent formation of all is called the Hawkesbury Sandstone (actually, it was not called the ‘Sydney Sandstone’ because that name had already been given to a rock unit in Nova Scotia, Canada).

Geological overview

The Hawkesbury Sandstone is a massive formation ranging in thickness from 34 m (in the lower Blue Mountains) to 240 m (in the Hawkesbury River district), composed largely of quartz sandstone, with about 5% shale. It covers an area of 12,500 square kilometres. Its most distinctive features are the inclined laminated cross bedding structures (see explanation below), the impersistent lens-like beds and the high proportion of quartz grains (typically 45–75%) which sparkle in some specimens due to silica overgrowths.

One idea of the origin of the Hawkesbury Sandstone involves sand accumulation in a braided river system originating from a large mountain range, similar to the modern Brahmaputra River in Asia. An alternative view describes a more subdued source and a somewhat more arid river system, akin to the modern Cooper Creek, Warburton and/or Diamantina River. Another interpretation favours a tidally influenced delta where herringbone-patterned crossbedding indicates bi-directional currents. This remains a controversial topic.

DID YOU KNOW?

The Ross Sandstone in Tasmania is the same age and type of rock as the Hawkesbury Sandstone and they were both deposited by a big river system that came all the way from Antarctica.

The distribution of the Hawkesbury Sandstone is indicated by the lightly shaded area in the map on the left (and it underlies the horizontal striped areas).

The formation was deposited during the Anisian stage of the Middle Triassic epoch which lasted from 247.2 million years ago until 242 million years ago. After burial and lithification, the sandstone was gentle folded, fractured and faulted, intruded by dykes and sills of basalt and uplifted, most notably in the west to form the spectacular Blue Mountains.

Cross bedding is common in the Hawkesbury Sandstone. This is a sedimentary feature that occurs at various scales, and reflects the transport of sand by currents that flow over the sediment surface (e.g., in a river channel) creating dune-like patterns with many thin parallel layers next to one another. These are called cross bedded laminae, because they form at an angle to the horizontal nature of the main bed. The image below shows cross bedding at Dee Why South headland, NSW. During deposition, the sand flowed from right to left.

flowed from right to left. Image courtesy M.J. Smith.

DID YOU KNOW?

Cross-bedding has been seen in the sediments on Mars.

Fossils are found in the shale lenses, which make up about 5% of the total volume of the Hawkesbury Sandstone and are typically 1 m to a few tens of metres in thickness. Fossils are best seen in old quarries which extracted shale to make bricks. The former Beacon Hill quarry is famous for its fish and insect fossils, while a shale layer quarried at Riverview for brickmaking contains fossil plants and rare fossil fish. One of the fish fossils is called Cleithrolepis granulata and an example is shown in the image below.

An attractive element of coastal exposures of Hawkesbury Sandstone is honeycomb weathering. This is the development of an intricate clustering of cavities on the surface exposure of sandstone inshore platforms, cliff faces and clifftop outcrops.

The weathering pattern may also be observed in artificial structures such as sandstone sea walls, breakwaters, tombstones and building stone. The weathering may mimic internal rock features such as cross-bedding. Hawkesbury Sandstone often displays a quite spectacular feature named ‘Liesegang Banding’. This is a rather vivid orange and brown circular pattern. The source is thought to be related to episodic movement of water through the solid rock which deposits iron oxide minerals (such as limonite) from time to time.

Indigenous context

Prior to European settlement, the Hawkesbury Sandstone was important to Indigenous people as evidenced by numerous rock engravings. It would have provided lookouts, camp sites, and overhangs (caves) for bad weather. The top of the NRG’s specimen is a natural weathered surface, and when in its original position at Pyrmont, would have been walked over by innumerable indigenous persons.

Sydney’s sandstone landscapes are built largely from nutrient poor, but iron-rich- and quartz-rich rocks, that support an incredibly rich flora, many of whose species benefit from the buffering action of iron against phosphorus toxicity. The floral diversities of sandstone heathlands and shrublands in places like the Royal and Ku-ring-gai Chase are only surpassed in Australia by those of south-west WA, an internationally recognised biodiversity hotspot. (Source: https://www.step.org.au/index.php/item/346-geology-of-the-sydney-basin).

Modern history and usage

Early travellers, like the soldier, teacher and author Alexander Harris (1805–1874) were impressed by the vertical sandstone cliffs and narrow entrance to Port Jackson (‘the precipitous wall of rocky coast… is broken by a gigantic chasm‘). It was named by Rev W.B. Clarke who wrote in 1878 that it is ‘a series of beds of sandstone, shale and conglomerate… which I have given the name of Hawkesbury rocks, owing to their great development along the course of the river basin of that name‘.

A 1924 description by H.G. Raggatt is slightly revised to read ‘the great beds of sandstone form the very foundation of the city itself. From North Head (image below) to Port Hacking this same sandstone meets the eye. Its weather-beaten face presents a stubborn rampart against the ceaseless pounding of the ocean; it forms the wild beauty of the Blue Mountain canyons, and the ledges over which streams of water descend in mighty leaps of sparkling cascades, scurrying to the sea‘. Cut sandstone, including the famous ‘yellow block’ specimen within the National Rock Garden, imparts warmth and dignity to city buildings and is a distinctive element in our urban architecture. It also provides us with a variety of other construction materials: sand from friable sandstones, breakwater armourstone, roadbase, rubble and rockfill. Sandstone is stable enough to stand in near vertical excavations, yet mostly weak enough to be excavated without blasting. Historically, it has also provided much of Sydney’s 19th century water supply, initially from the Tank Stream and later through Busby’s Bore.

Much of Sydney’s early sandstone architecture is associated with Lachlan Macquarie, Governor of NSW from 1810 to 1821, and his protégé the first government architect, Francis Greenway (1777–1837). Hawkesbury Sandstone was employed as a premium building stone in the early days of settlement in NSW and thereafter to the present day. The boom in sandstone architecture began after the 1850s gold rushes. The famous “yellow block” quarries named Paradise, Purgatory and Hellhole at Pyrmont commenced extraction about 1860. Significant Yellow Block Sandstone buildings include Sydney Town Hall, St Mary’s and St Andrew’s Cathedrals, the Art Gallery of NSW, NSW State Library, the Museum of Contemporary Art, the University of Sydney (image below) and many school buildings in Sydney.

The NRG’s sandstone block was sourced from the Minister’s Stockpile of stone at the Sandy Point, in southern Sydney, which is reserved for the restoration of monuments. It was donated by the NSW Department of Commerce. Approval was gained for the NRG to acquire one of the large blocks stored at the stockpile, shown below.

Want to know more?

Rust B.R. and Jones, B.G., 1987. The Hawkesbury Sandstone south of Sydney, Australia; Triassic analogue for the deposit of a large, braided river. Journal of Sedimentary Research (1987) 57 (2): 222–233. https://doi.org/10.1306/212F8AEE-2B24-11D7-8648000102C1865D

Gibbons, R., 2016. History as Landscape: Hawkesbury Sandstone and the Aboriginal Dreamtime https://www.academia.edu/22709271/History_as_Landscape_Hawkesbury_Sandstone_and_the_Aboriginal_Dreamtime

Author unknown. The Hawkesbury Sandstone Formation. http://www.adderley.net.au/geology/exhibition/04/04_02.html

Martyn, J., Geology of the Sydney Basin. STEP Matters 200. https://www.step.org.au/index.php/item/346-geology-of-the-sydney-basin#:~:text=We%20live%20in%20the%20Sydney,and%20erosion%20of%20its%20strata.

Vernon, R., 2010. Colour banding in Sydney sandstone. STEP Newsletter 157. https://www.step.org.au/images/STEPimages/STEPNewsletters/STEP-Newsletter_157.pdf

Whitehouse, J., 2016. Beacon Hill shale quarry, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia: Geologic insights into its strikingly preserved Triassic fossil assemblage. https://www.academia.edu/24223101/Beacon_Hill_shale_quarry_Sydney_New_South_Wales_Australia_Geologic_insights_into_its_strikingly_preserved_Triassic_fossil_assemblage

McNally, G.H. and Franklin, B.J. (editors), 2000. Sandstone City: Sydney’s dimension stone and other sandstone geomaterials. Monograph No 5, Environmental, Engineering and Hydrogeology Specialist Group, Geological Society of Australia.

Authors

Compiled by Mike Smith, Chair of the NSW Rock Selection Sub-Committee and Director, National Rock Garden, July 2020. Helpful comments from Matt Townsend and Marita Bradshaw have been incorporated.

These notes are mostly extracted from McNally, G.H. and Franklin, B.J. (editors), 2000. Sandstone City: Sydney’s dimension stone and other sandstone geomaterials. Monograph No 5, Environmental, Engineering and Hydrogeology Specialist Group, Geological Society of Australia.

Text from Greg McNally and David Branagan has been used directly.